Trademark law in plain English.

Part 1: Trademark Law 101

The reporter questions: who, what, where, when, why, how. But not in that order.

Why File Trademarks?

Purpose. The purpose of a trademark is to identify products and services with their providers. In other words, to be a “mark” of a “trade.” Consider the origin and purpose of the term “branding,” namely to identify your cattle from the others.

Best Practices. Best practices for trademarks include registering the trademarks that you are using and using the trademarks that you have registered.

Trademark Rights. In the US, registration gives the trademark owner numerous important rights, including the right to exclude competitors from using confusingly similar trademarks for similar products and services. (More on “likelihood of confusion” below.)

Prevention vs. Cure. It is much less expensive to prevent trademark issues than to cure problems after they arise. Not even considering litigation, the average dispute takes 2 months to lose/settle, 6 months to win, and 9 months to fight to a draw. The average US trademark application takes 12 months from filing to registration.

Where Should Companies Register Trademarks?

Current Business. In general, companies should register trademarks in the countries where they are doing significant business. If you have more than $500K/year of business in one country, then it makes sense to file your trademark in that country.

Future Business. If you plan to do significant business in a particular country, then you should file your trademark in that country.

Key Players. If you have a business partner, investor, or potential acquirer in a particular country, then you should also file trademarks in that country.

Who Can Register Trademarks?

Interstate Commerce. In the US, a trademark applicant must be using its trademark in interstate commerce (i.e. in multiple states or countries) in order to qualify for federal registration.

The Big Four. The average company has about four trademarks: their name, their logo, the name of their primary product or service, and their tagline.

Registered vs. Unregistered. There are two ways to acquire trademark rights. First, using a trademark gives you common law (unregistered) rights where and how you use your trademark. Second, filing a trademark application give you a de facto use date as of the filing date. Unregistered trademarks should be marked with the “TM” symbol, registered trademarks with the “circle-R” symbol (®).

What Can Be Registered As A Trademark?

Mostly Words And Logos. A trademark is anything that identifies the source of particular products and services. While “anything” can include oddities like colors, scents, and sounds, the vast majority of trademarks fall into two basic categories: words and logos. Of the 4 million trademarks in the USPTO’s database, about 70% are word trademarks (mark drawing codes 1, 4), and 30% are logo trademarks (mark drawing codes 0, 2, 3, 5).

Oddball Trademarks. Fewer than 300 total trademarks are of type “other” (mark drawing code 6), which mostly includes sound trademarks, including Darth Vader breathing, Homer Simpson’s “D’oh!” exclamation, and the famous NBC chime sound (the notes G, E, and C).

How And When Should Companies Register Trademarks?

Search Then File Then Launch. Ideally, a company would conduct a trademark clearance search after choosing – but before using – its trademark. It is much easier to change a name before launching a product or service than after. And it is much easier to avoid trademark conflicts if you do your homework and conduct a proper trademark search.

Words vs. Logos. Searching word trademarks is relatively straightforward. Searching logo trademarks, not so much. The two best options for searching logo trademarks are the USPTO’s database and image-based search engines (sometimes called reverse-image search engines). The USPTO publishes the US Trademark Design Search Code Manual, which assigns six-digit numbers (design search codes) to text descriptions of various graphic elements. If you craft your logo trademark search too broadly, then you’ll have hundreds (if not thousands) of trademarks to review. If you craft your search too narrowly, then you’ll likely miss something important.

US Then Foreign. Under the Madrid Protocol (an international treaty), foreign trademarks filed within 6 months of a parent application are treated in the foreign country as if filed on the date of the parent application. Absent objections from designated countries, Madrid Protocol trademark applications mature into registered trademarks 18 months from the parent filing date.

Part 2: Trademark Law 201

More subtle trademark issues.

Likelihood of Confusion. OK to use? OK to file?

Registration vs. Ownership. Many trademark owners misunderstand the rights that a registered trademark gives them. You do not get to “own” your trademarked term. You only get to enforce your trademark rights when the legal standard of “likelihood of confusion” has been met, and that only occurs when both the trademarks and the products/services covered by them are close enough.

First Impression. Like art, trademark lawyers know “likelihood of confusion” when they see it.

Search Results Options. Worst to best:

D. Not OK to use, not OK to file (belongs to somebody else).

C. Not OK to use, OK to file (rare, ITU, under the radar).

B. OK to use, not OK to file (likely descriptive).

A. OK to use, OK to file (best case).

What makes a strong trademark?

Trademark Strength. Trademarks need to be distinctive in order to qualify for registration in the Principal Register. Some marks may be able to acquire distinctiveness and can be placed in the Supplemental Register. The following categories of marks are listed from strongest to weakest.

A. “Fanciful” marks are the strongest trademarks. Fanciful marks consist of one or more made-up words. Examples include EXXON, KODAK, VERIO, and XEROX.

B. “Arbitrary” marks are very strong trademarks. Arbitrary marks consist of real words that have nothing inherently to do with the product/service being sold. Computers have nothing inherently to do with apples, so APPLE is a good trademark for a computer company. Examples include APPLE (computers), AMAZON (books), and SUN (computers).

C. “Suggestive” marks are strong trademarks. Suggestive marks consist of real words that suggest a quality that the company or its products/services stand for. Greyhounds suggest speed, so GREYHOUND is a good name for a bus company.

D. “Descriptive” marks are weak trademarks. Examples include “Computer Equipment Store” and “Word Processor.”

F. “Generic” marks are those that refer to a category of goods/services instead of a particular company’s products/services. Some marks used to be distinctive but have become generic. Examples of “genericized” former trademarks include ASPIRIN, LINOLEUM, ESCALATOR, and NYLON.

Options for weak trademarks: Principal Register vs. Supplemental Register.

Principal Register vs. Supplemental Register. The USPTO has two lists (or Registers) of trademarks. The Principal Register is for marks that are distinctive. The Supplemental Register is for marks that are not (or not yet) distinctive enough. The benefits of registration in each is as follows.

Registration in the Principal Register provides:

(a) Notice to others that the mark is taken.

(b) Right to put the “circled-R” symbol (®) after the mark.

(c) Right to recover triple damages and attorneys’ fees from an infringer.

(d) Exclusive use of the mark (excepting prior use).

Registration in the Supplemental Register provides:

(a) Notice to others that the mark is taken.

(b) Right to put the “circled-R” symbol (®) after the mark.

(e) Right to re-apply for registration in the Principal Register after five years of continuous use.

Options for weak trademarks: the “Microsoft Windows” approach.

Descriptiveness – The “Microsoft Windows” Approach. When a trademark is at least partially descriptive, we recommend adding your core brand to the trademark and filing it as a combined mark. We call this the “Microsoft Windows” approach.

(1) First, register the strong trademark (Microsoft®).

(2) Second, register the combination trademark (Microsoft Windows®).

(3) Third, start using the second trademark alone (WindowsTM).

(4) Fourth, register the second trademark (Windows®).

Stuff needed for filing: the trademark, the goods/service, the specimen.

Goods/Services. You can see how the USPTO classifies trademarks by searching for keywords in the US Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual.

Specimens. In order for something to serve as a trademark, it needs to be a source-identifier for the specified goods/services. A specimen is an example of the mark being used as a trademark in interstate commerce in connection with the specified goods/services. On your specimen, the trademark should be prominent and should stand out from non-trademarked terms. Each trademark specimen needs to show:

(1) the trademark,

(2) being used as a trademark,

(3) on the goods (or, in the case of services, near the description of the services),

(4) that are described in the trademark application.

For goods (including software), acceptable specimens include product labels, tags, containers, displays, instruction manuals, and photos of the mark as actually used on or in connection with the goods.

For downloadable software goods, an acceptable specimen may be a screen shot of the mark as actually used in the software.

For services, acceptable specimens include newspaper and magazine advertisements, brochures, billboards, handbills, direct-mail leaflets, menus, website screen-shots, and the like. Since websites are inherently interstate and inherently relate to commerce, a good specimen would be a screen shot of a page from your website showing the mark being used as a trademark.

Budgeting: Costs of searching for and registering trademarks.

You should budget:

- About $1000 for each trademark search.

- About $2000 for each US trademark application.

- About $3000 for each foreign trademark application (except Europe).

- About $4000 for each European trademark application.

- About 75% of filing costs for all renewals every 10 years.

- Plus $1500 for US renewals at year 6.

Best Practices: Lather, rinse, repeat.

Trademark protection is a process, not an event. You should:

- Use what you register.

- Register what you use.

- Trademark glossary (and genesis: LawyersForHumanBeings.com).

- Search -> file -> use.

- Beware of website redesign.

- Trademark classes vs. business focus.

- Think like ranchers. What are you branding?

Related Articles

- How To Build A Startup: One Board At A Time, Be Yourself, Get Plants (2016-06-15)

Top 11 tips for entrepreneurs. - The Who, What, Where, When, Why, And How Of Patents (2014-03-12)

Patent law in plain English. But not in that order. - Top 10 Things BigLaw Patent Lawyers Don’t Want You To Know (2012-09-26)

And won’t tell you. Srsly. - Domain Name Law 101 (2008-01-28)

White hat domainers are not black hat cybersquatters.

Erik Heels (Attorney, Entrepreneur, Disruptor) claims to publish the #1 blog about technology, law, baseball, and rock ‘n’ roll at ErikJHeels.com. Brevity is not his strong suit.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: In the summer of 2025, Clocktower Intern Mark Magyar used artificial intelligence (AI) software to shorten over 100 Clocktower articles by 17%. The shortened articles are included as comments to the original ones. And 17 is the most random number (https://www.giantpeople.com/4497.html) (https://www.clocktowerlaw.com/5919.html).]

* The Who, What, Where, When, Why, And How Of Trademarks

Trademark Law in Plain English

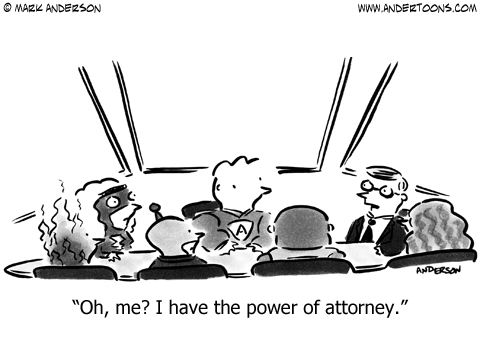

Superhero business meeting: Oh, me? I have the power of attorney.

Part 1: Trademark Law 101

Why File?

Trademarks identify products/services with their providers. “Branding” comes from marking cattle to distinguish ownership.

Best Practices: Register what you use; use what you register.

Trademark Rights: U.S. registration grants rights to block confusingly similar marks.

Prevention vs. Cure: Prevention is cheaper. Average disputes: 2 months to lose/settle, 6 to win, 9 to draw. U.S. trademarks take ~12 months to register.

Where to File:

Current: File in countries with >$500K/year sales.

Future: File where you plan major business.

Key Partners: File where partners/investors/acquirers are based.

Who Can File?

Must use mark in interstate commerce. Typical companies register 4 marks: name, logo, core product/service, tagline.

Registered vs. Unregistered:

Use = common law rights (mark with ™). Registration = federal rights + ® symbol.

What Qualifies?

Mostly words/logos. Oddities include sounds (NBC chimes), scents, colors.

How & When to File:

Search → file → launch. Searching early avoids costly rebrands.

Words: Easier to search.

Logos: Use USPTO’s Design Code Manual or reverse image search.

File U.S. first; use Madrid Protocol for international filings (within 6 months).

Part 2: Trademark Law 201

Likelihood of Confusion:

Rights arise only when similar marks/products cause confusion. Lawyers “know it when they see it.”

Search Outcomes (worst to best):

D. Not OK use/file.

C. Not OK use, OK file (rare ITU).

B. OK use, not file (descriptive).

A. OK use/file.

Strength Spectrum:

A. Fanciful (made-up): EXXON, KODAK.

B. Arbitrary (real words): APPLE (computers).

C. Suggestive: GREYHOUND (buses).

D. Descriptive: “Word Processor.”

F. Generic: Aspirin, Escalator.

Registers:

Principal: Full rights + ® + triple damages.

Supplemental: For weaker marks; can reapply to Principal after 5 years.

Microsoft Windows Approach:

File strong brand (Microsoft®).

File combined (Microsoft Windows®).

Use second alone (Windows™).

Register second (Windows®).

Specimens:

Must show the mark identifying goods/services. Examples: labels, screenshots (software), ads/webpages (services).

Budgeting:

$1K per search.

$2K per U.S. filing.

$3K per foreign filing.

$4K for Europe.

Renewals: 75% filing cost (every 10 yrs) + $1.5K U.S. (yr 6).

Ongoing Best Practices:

Search → file → use.

Use registered marks.

Register active marks.

Watch redesigns (specimens!).

Think like ranchers: brand what matters.

Related:

How to Build a Startup (2016)

Patents in Plain English (2014)

BigLaw Secrets (2012)

Domain Law 101 (2008)